Breathing is one of the most natural functions of the human body. How we perform this life-sustaining task is important, especially given the fact that we breathe twelve to fourteen thousand times per day! Many of us have forgotten the authentic, diaphragmatic breathing pattern established shortly after birth and have replaced it with dysfunctional breathing patterns. Focusing on diaphragmatic breathing is a key component to One on One’s corrective exercise, strength training, and athletic performance training programs.

Dysfunctional breathing, characterized as shallow breaths coming from the upper chest and shoulders, can lead to a number of negative health outcomes:

- Postural imbalance (forward-head position, elevated shoulders, hunched upper back)

- Neck and shoulder pain

- Fatigue

- Dizziness

- Reduced pain threshold

- Anxiety

Diaphragmatic breathing, on the other hand, is a gateway to health benefits such as improved nerve and muscle function, proper immune system function, enhanced relaxation response, and increased metabolism. It truly plays a major role in a successful exercise experience.

At One on One, we talk a lot about maintaining a ‘neutral spine’ as we exercise. Neutral spine is maintained by activating the deep core muscles that stabilize our spine. One of these deep core muscles is the diaphragm, which has a dual role as a respiratory muscle and a stabilizer muscle. When the diaphragm works in unison with rest of the core stabilizers, they create an ideal environment for spinal stabilization, helping to protect our lower back.

A special emphasis should be placed on diaphragmatic breathing during strength training exercises such as deadlifting, lunging, squatting, kettlebell swinging or overhead pressing. The movement will feel stronger, and the lower back will be protected.

Diaphragmatic breathing is also a key component to improving mobility. Taking long, slow, diaphragmatic breaths, brings the body into a relaxed state, allowing muscles and joints to move with ease. Pushing to create a stretch at a maximal threshold will alter one’s breathing pattern, and the body will perceive that as stress. As a result, breathing patterns become altered and the stretch produces minimal results. Stretching should be done at three-fifths of your maximal movement: the stretch should not feel like a one (no stretch) or a five (intolerable stretch). It should be enough to create a stimulus but not alter the breathing pattern. This approach produces the best results in improving one’s mobility and monitoring your breathing can help ensure you are in the right range.

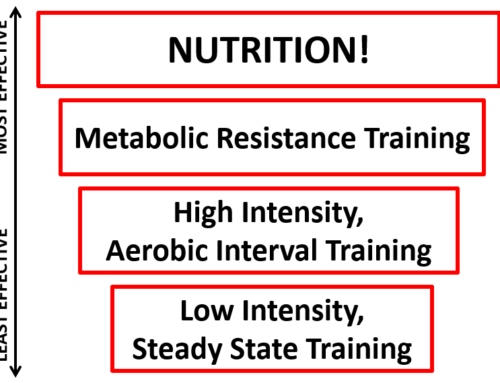

Breathing needs to remain in check during highly intense conditioning sessions as well. Intervals, met circuits, group training classes, finishers, and other intense workouts can create a high demand for our bodies to perform. As a result, our breathing patterns change. We all know the feeling of having to gut out the last three reps; the last thing that we are thinking about is a proper breathing pattern. Our bodies are just trying to finish the challenging task. Some strategies to combat the dysfunctional breathing created by this training include:

- Take diaphragmatic breaths during the rest intervals and water breaks.

- Make an effort to do crocodile breathing at the end of the workout and/or another time during the day.

If you’re not sure that you’re breathing correctly, speak with your trainer and start to re-learn this essential bodily function.